- Home

- LYNDA BARRY

CRUDDY Page 3

CRUDDY Read online

Page 3

She thought long and hard about what to do. Dr. Cush gave the mother a little something to help her get started elsewhere. Not much. Not nearly enough. But she took it, bought a sky blue Rambler American, packed up Julie and didn’t look back. Do they remember us there anymore? The family that became unhinged and blew away?

I have wondered too why the mother decided to make the identifying call. Maybe she was afraid of what I would say if I finally started talking. How I might tell the truth, that it was her who shoved me into the backseat of his car in the middle of the night. Her who piled the clothes on top of me and said if I said one single word, if I made a peep to let him know I was back there, she would pull my eyes out.

Or maybe she called because she could not stand to see me getting all of the publicity. She had always wanted her picture in the newspaper. Maybe she just could not stand the thought of me hogging all the action.

In the little teeny grease spot on the map where I was born the name Rohbeson meant quality meat. Rohbeson’s Slaughter and Custom House was famous for five counties. Rohbeson’s methods were strictly Old World. Everything done by hand. The rounding, knocking, bleeding, gutting, skinning, splitting, dressing, aging, curing, pickling, packing, bone and hoof boiling, all of it done right on-site.

The father slammed his hand down on the kitchen table and made the forks and knives jump. He said, “I’ll challenge anyone to come up with better tasting meat. That shit what’s coming out of Chicago now? Out of those big houses? That ain’t meat. I don’t even know what to call it. It’s what you get when you pack half-dead cattle nose to asshole, scare the living hell out of them with shock prods, blow their brains out with a bolt gun louder than a cannon and then hoist them up to bleed ’em on a chain line.”

“Uh-huh,” said the mother, yawning and stirring a tiny spoon into a jar of Julie’s baby food. Julie was sick. Something was very wrong with her. She was giving off smells.

The father was taking straight pulls out of a bottle of Old Skull Popper. “With line crews, it’s output, output, output. They don’t cull. A carcass comes down the belt with tumors as big as your head and worms wiggling from hell to breakfast and you know what they do? Send it down the line. Let the next bastard worry about it. They got the inspectors in their back pockets, they’d stamp USDA on a dead rat. You know what USDA stands for? You Stupid Dumb Ass. That’s what a customer is who buys that shit. Them line men piss right into the pickle vats. I know for a fact they do.”

“Except it’s a ‘Y’,” said the mother.

“What?”

“‘You’ begins with a ‘Y’.” said the mother. “Not a ‘U’.”

The father stood to inherit Rohbeson’s Slaughter when Old Dad died. He was next in line. He was the only man in line. The last standing Rohbeson. “And he just sold it out from under me. Never said word one. I was out there running things, up to my nuts in blood and sawdust every day, telling him we were going to turn it around. ‘Those big packing houses got nothing on us, Old Dad. The stores are going to come back begging, Old Dad.’ And all that time he was nodding, blowing smoke up my ass.

“We could have goddamned turned it around! You know that half the cuts we do you can’t even find anymore? A whole world has just died out and no one gives a damn about it. Pretty soon you won’t see an independent butcher anywhere. Gone. Shit. Gone.”

“Uh-huh,” said the mother.

“I’m glad the bastard hung himself. If it was up to me I would have left him swinging with the carcasses right where he was. I would never have cut him down. I would have bled him and dried him and made him a goddamned mascot. A goddamned tourist attraction. Come on down over to Rohbeson’s Slaughter and meet Old Dad. Get your picture taken with him and have a free hot dog.

“Bastard sold it all out from under me. Paid off the mortgages. Packed what was left over in three Samsonite suitcases, cash money delivered to settle the last of what he owed. Note said, ‘Sorry, son. But at least I’m not leaving you in the hole.’ ”

“Well, that is something,” said the mother. Julie’s head was hanging forward. She was asleep and her face was sweating.

“SOMETHING?” screamed the father. “It’s SQUAT! Not even a goddamned life insurance policy! SQUAT!” His hands bounced some additional slams onto the table and then he stood up.

This was our last dinner together. We were eating chipped beef on toast.

“You better start looking for a job,” said the mother. “We’re supposed to be out of here by the first.”

“JOB?!” shouted the father. The night went on like that. And the next day the wife of Ardus Cardall was rushed into St. Martha’s, the tiny hospital where the mother worked. Someone had blasted her arm off point-blank with a hunting rifle. When the mother came home from work she was squinting hard at the father who squinted right back.

He said, “Marie Cardall. She going to make it?”

The mother said, “What do you think?”

The newspaper version of the story said witnesses saw a man in Elkwood-issue coveralls near the house the night an escapee bulletin went out on the wires. Marie’s car was stolen and no one knew what else. She was shot with her husband’s rifle. The newspaper version said her husband Ardus was being questioned about it.

“His alibi is tight,” said the father. “Can’t get much tighter than being in jail yourself when the crime occurs. She going to pull through?”

The mother said, “What makes you so interested?”

“Hey,” said the father, “I don’t give a damn about Marie Cardall. I’m just making conversation.”

Suspicion was cast on Ardus Cardall because he was bitter about his wife turning him in and testifying against him. Bitter wasn’t the word. And he was a string-puller.

It was Marie Cardall who contacted the police when Ardus came home from work and told her he might have buried the little boy that was lost, the boy the town was turning itself inside out about. He told Marie there was a pretty good chance he buried the Leonards boy alive in concrete while he was pouring the foundation for the new church. He said that by the time he noticed there was nothing he could do. The boy was gone. So he just kept pouring. He told Marie he was just hoping the whole thing would somehow blow over.

“And she turned him in,” said the father.

“She was right to report him,” said the mother.

“Well, Ardus saw it differently.”

“For god’s sake.”

“If you think that she went to court because she gave a damn about that Leonards boy you are ignorant as living hell.”

“Why, then?” snapped the mother.

“Figure it out. It ain’t long division.”

The mother snorted. “No. I guess it ain’t.” Saying “ain’t” with special emphasis.

“Well?” said the father. “Did she make it or not? Is Mrs. Cardall still among us?”

“You tell me.”

“My guess is she pulled through.”

“Ha,” said the mother. “Ha-ha. You’re funny.”

It was that night she shoved me into the backseat of his car and told me not to show my face. It was that night he told her he was leaving on a business trip and would probably be gone for a while.

Chapter 6

ICKY CUT along the top of the embankment, ducking and keeping close to the Cyclone fence that ran through the half-dead pine trees. Different P.E. classes were coming out onto the field. Different gym teachers were blowing black plastic whistles and shouting. Fifth period. First time I ever skipped.

We kept going. The Cyclone fence ran out. We came to the far, far end of the school and then crossed over into where everything was growing wild. The area people called no-man’s-land, because it was between the school and the reservoir. There wasn’t anything there but a decrepit old outbuilding, in a place everybody called the Dip. It was at the bottom of two embankments and the sticker bushes grew high all around. There was no direct path down, but little juvenile delinquent trails zigz

agged through the Scotch broom and the disturbing trash you always find in abandoned places along with the drifting smell of human pee.

Vicky went very fast through the paths, not pausing at all when the fly families lifted around her and then settled and then lifted again. It was the beginning of September, still very warm for Cruddy City, but at the bottom of the embankment it was bright and actually hot. There were piles of rabbit evidence, and a pile of someone’s old stiff clothes giving off a close smell, like in a hot secondhand store, and there was the smell of the outbuilding itself. “I have to go bad,” Vicky Talluso said. “Guard me.” She squatted down.

The building was wooden and rotting with a half-falling-in roof. A curved, military-style roof, the kind you see on the buildings at Fort Stilacoomb. There were old NO TRESPASSING signs nailed on it and the paint was peeling off in long green scabs. Along the top near the corroded roof edge were three rows of shiny small-paned windows painted black from the inside and mostly broken. Pigeons flew in and out constantly. On the door someone had carved the words BIG DICK MEL.

Everything was seeming very quiet and the sun was sending down rays that made everything look washed out. Vicky stood back up and looked at me. “You paranoid?”

“No.”

“Because I hate paranoid people. If you are paranoid you better tell me right now.”

“I’m not.”

The door was big, like the door on a barn. It had some rusted link chains across it, but Vicky knew where to pull so that a gap opened up wide enough to push through. “You,” she said. “You first. I’ll hold it for you.”

I hesitated and she saw it. I hesitated even though the father told me a thousand times, DO NOT HESITATE. NEVER, EVER HESITATE. The father said hesitation is for your average man and your average man always loses. Vicky made a tiny move of impatience and it freaked me forward. I squeezed myself into the blackness. It felt like all the light in the world got sucked away.

The smell of the building was thick and rank. It was moist. The smell of rodents and pigeons and rotting straw. I felt the ache of my eyes dilating too fast. In the ancient days of our school, the building was where the maintenance men kept things. It was where the archery bales were stored when people still took archery in gym. The famous story was that the targets got hauled across the field and set in rows and sophomores stood holding bows and sharp arrows waiting for the gym teacher to signal the moment to shoot. And one time a dog wandered onto the field and before the teacher could call it away one of the kids just shot it. And then everyone was running to help the dog and the kid shot another kid and he just kept on shooting until he got tackled. He said he wasn’t a disturbed person. He said he was just a plain normal person that sometimes had to kill people with arrows.

I didn’t know if the story was true or not. There are a million stories that float around a school. But as my eyes adjusted I saw putrid stacks of gray hay with torn bull’s-eye targets still hanging on them.

Vicky found a place to sit. Shafts of light fell down around her from holes in the roof. I saw the familiar glue-sniffer brown paper bags laying around. There were the magazines showing nudeness. Pink flobs of skin and black wiry hair. A leak of sunlight slid across Vicky’s back as she leaned down to look at one closer. Tilting her head at the page like she was trying to read a message in bad handwriting. “Look,” she said. A picture of a man having an interaction with a slime flower fold. “Do you know that Jesus loves him just as much as he loves you and me? Isn’t that cracked? Sit down. I want to give you a transformation. I am so good at transformations.”

In the old days of the father I was in many situations where everything around me was screaming DANGER! DANGER! FREAK OUT AND RUN! but he taught me to go forward. He taught me to remember I was Navy all the way and to go forward without fear. Compared to what I have seen in my life, Vicky Talluso’s world was nothing. But I was out of practice. It had been a long time. I was rusty and all I needed was a little oil. That is what the father would have said before he passed me the flat bottle of Old Skull Popper. “Clyde, you have nothing to fear ’til you run out of beer.”

Mostly he was right. Mostly what looked like a horrifying scene at first turned out to be nothing at all. Like the transformation Vicky wanted to give me. All she meant by it was she wanted to put makeup on me. She said there was no reason for me to go around looking like a skag when I didn’t have to.

She pulled out a pink rattail comb and moved me into a pool of light. “No offense but your hair is horrible. You need to grow it, OK? You will look a lot better with long hair. I am going to do beauty for a living. I just have it in me. I can just look at a person and tell exactly what to do.” The feeling of her combing my hair made a nice sensation in the back of my throat.

She said, “Do you have a boyfriend?”

“No.”

“Did you ever have one?”

“Nuh-uh. No.”

“Well, when I finish this, I know the perfect guy for you. Do you get high? You ever drop before?”

“No.”

“Because you’re against it?”

“I’m not against it.”

“Then because no one ever got you high before, right?”

“Right,” I said.

“God. You are going to be soooooo thankful that you met me. You are going to love me so much after today. You haven’t ever done anything exciting, have you?”

“Partly I have.”

“What?”

“Well, I killed somebody once. A couple people, actually.”

She was snort-laughing. I felt her breath on the back of my neck. It had a scent that surprised me. Under the cig smell there was a cherry cough drop smell I hadn’t noticed before. Part medicine, part pretty candy.

She said, “You killed people?”

“Yes.”

“Yessssss. God, you are sick. How. How did you kill them?”

“With Little Debbie.”

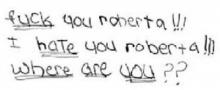

She was laughing again. Pushing my head forward and ratting my hair high. She said, “Roberta, this guy I was telling you about? He is going to love you.”

Chapter 7

HE FATHER drove through the darkness. He drove and he drove. I curled up in the well of the backseat floor and felt the vibrations of the road beneath us. The father sang with the radio. He had a decent voice. He thought he could have been a famous singer and maybe it’s true.

He talked to Old Dad. Old Dad, you bastard. Old Dad, you lying sack of shit. He glugged Old Skull Popper and every once in a while he talked to Marie Cardall, another sack of shit, just like her husband. He threw cig after cig out the open window and a couple of them got sucked back in and landed in the backseat. I smelled the smoke before he did. And then he shouted, “SON OF A BITCH!” and slammed on the brakes. I was thinking we were on fire, but it was a roadblock.

Troopers came to the car from four directions with strong flashlights and the flying night bugs were going wild. The father hated troopers. He hated all cops, but troopers most of all.

“Hands on the steering wheel where I can see them.” A blinding flashlight beam shot around the inside of the car and hit me in the eyes. When the trooper saw me he lowered it. He said, “Sorry there, sweetheart. Don’t be scared.” The father whipped his head and when he saw me his eyes went wide.

“Daddy,” I said. Reaching up my hands to him just like he taught me. If we were ever stopped by cops it was what I was supposed to do. Call him Daddy. Act scared. Start to cry. And if I could manage to throw up, that would be handy.

“Aw, honey, I’m sorry,” said the trooper. “Didn’t mean to scare you. Did I wake you up?”

“It’s OK, ’Berta,” said the father, and he reached back for me and pulled me over into the front seat. There were times when it was handy for me to be a girl. It was one of those times. I pushed my face into the father’s shoulder and wondered if I should barf or not. It would have been no problem. I’d been feeling carsick for miles.

“I’m sorry to bother yo

u, sir. Can I see some ID?” The trooper leaned his head in the window.

“I’m looking,” said the father. He was digging in his pockets for his wallet and trying to keep his face down so the Old Skull Popper fumes wouldn’t rise up the trooper’s nose. I could see how nervous he was. I said, “Daddy?” I pointed to the torqued-out rectangle of leather on the dashboard. “You looking for that?”

“Oh thank Jesus. Yes. Yes, baby doll. Thank-you.” The father handed his license the trooper and said, “She’s the brains of this operation.”

The trooper smiled and shined his flashlight into the backseat again.

“Something burning in there?” Wispy smoke was curling up from the clothes.

The father yanked the clothes out of the backseat while the trooper took his license and registration back to call it in and the other men shut their flashlights off and went back to talking with one another. The father threw a few looks my way and shook his head a couple of times and laughed under his breath. “Missed your old man, huh, Clyde? Couldn’t stand to see me go, is that right? Don’t worry. I’m not going to whip you. You just saved my ass, son. When we get out of this, I’m going to buy you a hamburger.”

The father found the smoldering clothes and stamped them out. The trooper came back with his ID and handed it back through the window. He had a warm bottle of RC. “This is for your little girl. Wish it was cold for her.”

“It don’t matter,” said the father, passing it my way. “She’s a garbage gut. She’ll eat and drink anything you put in front of her.” I hated pop but I took a drink anyway.

The father said, “You hunting that escapee from Elkwood? Is that what this is about?”

The trooper lifted his eyebrows. “You know something about it?”

“Heard he blew her arm off point-blank. Heard she was bled out terrible by the time they brought her in. My wife worked on her. She’s a nurse at St. Martha’s.”

CRUDDY

CRUDDY